News

New study confirms Cambodia’s last leopards on brink of extinction

We are not sure whether to be excited or horrified to have discovered that our search for clouded leopards in Cambodia caused us to find the last enclave of ‘common’ leopards in Eastern Indo-China, writes David Macdonald.

Of course we are excited to have found this last cluster of leopards, but the name ‘common’ sits uncomfortably on the beautiful shoulders of an animal, once abundant, that is now horrifying rare. I first went to this part of Cambodia with WildCRU’s Dr Jan Kamler – a remarkable biologist who specializes in seeking out rare carnivores in the remotest corners of Asia. We were searching for clouded leopards and dholes and the truth is we didn’t get far with either. However, every cloud has a silver lining, and we set up splendid studies of both golden jackals (soon to be published) and leopards (published this week). In the following years the leopard study was led by WildCRU’s Susana Rostro-Garcia, now well through a remarkable doctorate on the species, and Jan became Panthera’s Asian leopard specialist.

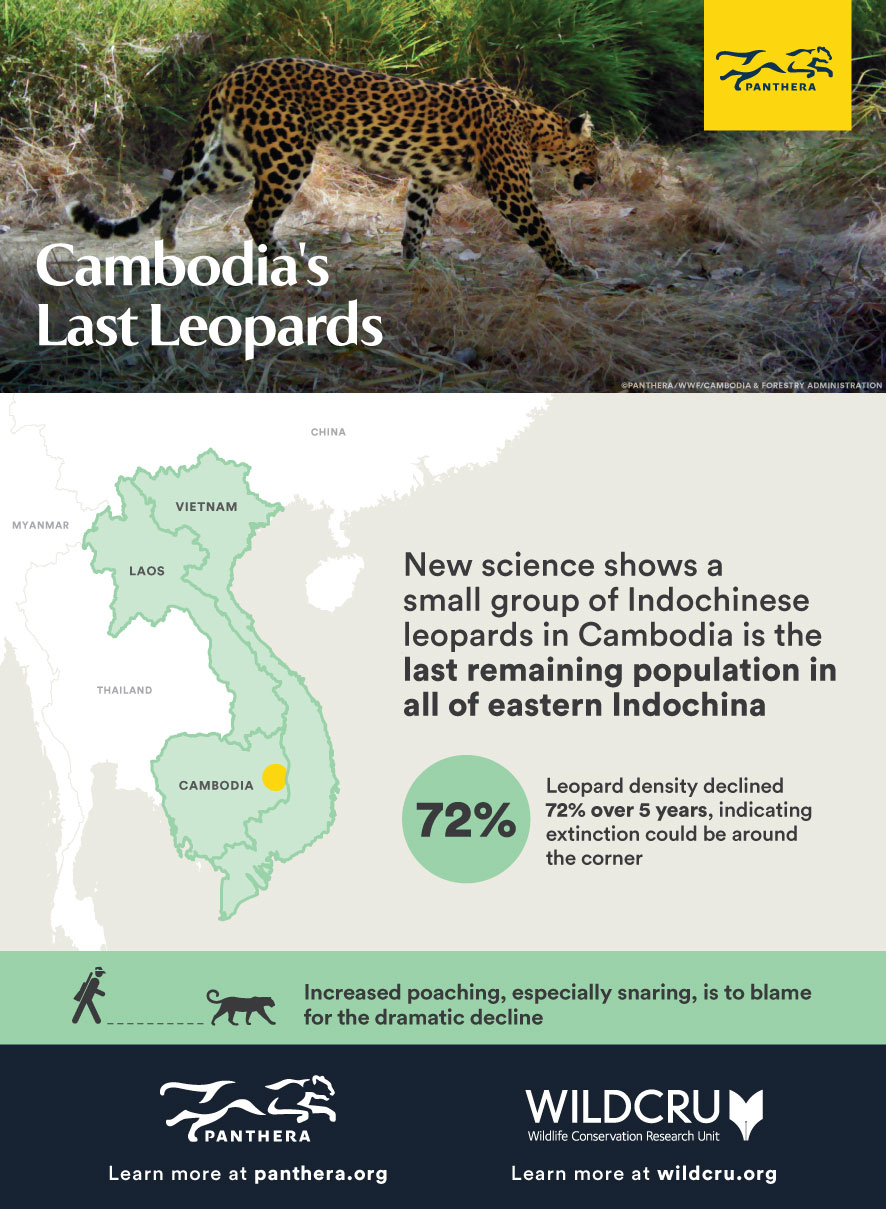

Our study, reveals that the last breeding population of leopards in Cambodia is at immediate risk of extinction, having declined an astonishing 72% during a five-year period. The population represents the last remaining leopards in all of eastern Indochina – a region incorporating Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam. These results are published in the Royal Society Open Science journal by Oxford University’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU), Panthera – the global wild cat conservation organization, WWF-Cambodia, the American Museum of Natural History, and the Forestry Administration of the Ministry of Agriculture Forestry and Fisheries of Cambodia.

Carried out in Cambodia’s Eastern Plains Landscape, the study revealed one of the lowest concentrations of leopards ever reported in Asia, with a density of one individual per 100 square kilometers. Increased poaching, especially indiscriminate snaring for the illegal wildlife trade and bushmeat, is to blame for the dramatic decline.

Jan Kamler, now Panthera Southeast Asia Leopard Program Coordinator, stated, “This population represents the last glimmer of hope for leopards in all of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam – a subspecies on the verge of blinking out. No longer can we, as an international community, overlook conservation of this unique wild cat.” David Macdonald added “Leopards are a monument to opportunism, adapting to habitats from desert to urban jungle, but their adaptability risks a deadly complacency: people think – “oh, leopards will be fine”. They won’t! Almost everywhere they are doing worse than people thought, and our findings show that in SE Asia they are heading for catastrophe”.

We were intrigued to find that the primary prey of the Cambodian leopards was banteng – a wild species of cattle whose adults weigh up to 800 kilograms (1,760 pounds). In particular, male leopards targeted this large ungulate, making this the only known leopard population whose main prey weighed greater than 500 kg (1,100 pounds), more than five times the leopard’s mass. Our interpretation is that Indochinese leopards have opted for this prey following the extirpation of tigers from the region in 2009, which created a predatory void for the opportunistic and highly adaptable species.

Prompted by the study’s findings, Panthera and WildCRU are working with local and national collaborators to increase effective law enforcement and monitoring of this region, which will include the use of Panthera PoacherCams, and strengthen environmental laws to develop strictly protected conservation zones and increased fines for poachers.

Historically found throughout all of Southeast Asia, the Indochinese leopard has lost 95% of its range and is likely to be classified as Critically Endangered by IUCN later this year. A separate study recently led by Susy Rostro-Garcia and involving a team from WildCRU, Panthera and others estimates just over 1,000 breeding adult Indochinese leopards remain in all of Southeast Asia. However, just 20-30 reproductive individuals remain in eastern Cambodia, representing the last hope for the leopard’s future in eastern Indochina.

Poaching for bushmeat and the illegal wildlife trade, habitat loss, prey decline due to bushmeat poaching, and conflict with people are to blame, creating a deadly cocktail of threats facing leopards in Asia, and around the globe.

WildCRU scientist and lead author, Susana Rostro-Garcia, stated, “Much of the snaring in Cambodia, and across Southeast Asia, is driven by the rising demand for bushmeat. Wild landscapes are covered with thousands of snares set to catch wild pig and deer to supply bushmeat markets. Unfortunately, these snares also negatively impact many other species, with leopards and other wildlife often caught as by catch, and their valuable parts removed and sold to illegal wildlife traders.”