News

David Macdonald reports on a new study revealing that affluent countries commit less to wildlife conservation than the rest of the world.

Some countries are more committed to conservation than others, a new Oxford University research collaboration has found. The findings are published in Global Ecology and Conservation.

In partnership with Panthera, and colleagues in institutions from Australia to the USA, WildCRU researchers investigated how much, or little, individual countries commit to protecting the world’s wildlife. By comparison to the more affluent, developed world, we found that biodiversity appeared to be a higher priority in poorer areas such as the African Nations, who commit more to conservation than any other region.

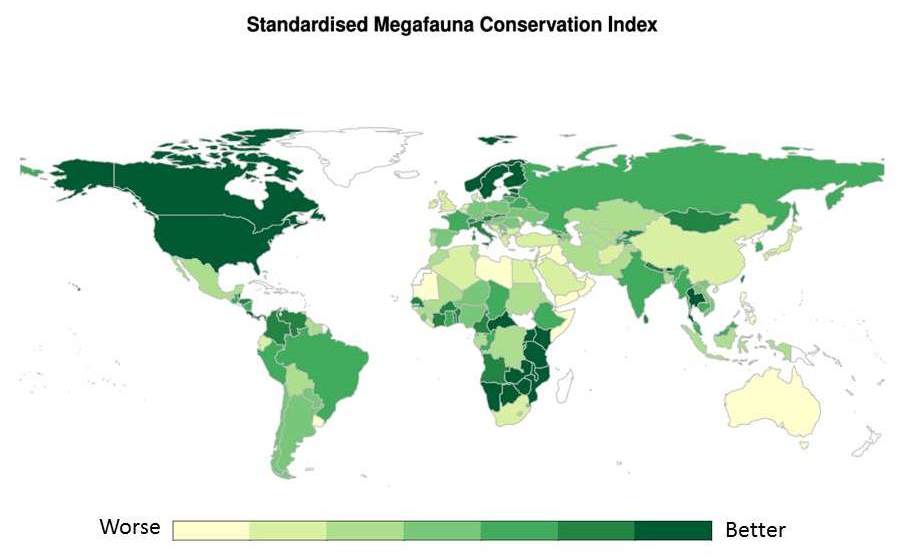

The collaboration was led by Peter Lindsey, a frequent partner in our research, and the team created a Mega-Fauna Conservation Index (MCI) of 152 nations from around the globe, to evaluate their conservation footprint. Since a high proportion of mega-fauna species, such as tigers, leopards, gorillas and elephants face extinction, we focussed on the protection of large mammals. The benchmarking system evaluated three key measures: a) the proportion of the country occupied by each mega-fauna species that survives in the country (countries with more species covering a higher proportion of the country scoring higher); b) the proportion of mega-fauna species range that is protected (higher proportions score higher); c) and the amount of money spent on conservation – either domestically or internationally, relative to GDP.

According to our index, poorer countries tend to take a more active approach to biodiversity protection than richer nations. Ninety per cent of countries in North and Central America and 70 per cent of countries in Africa were classified as above-average in their mega-fauna conservation efforts. Despite facing a number of domestic challenges, such as poverty and political instability in many parts of the continent, Africa was found to prioritise wildlife preservation, and contribute more to conservation than any other region of the world. With Botswana, Namibia, Tanzania and Zimbabwe topping the list. By contrast the United States ranked nineteenth out of the twenty top performing countries. Approximately one-quarter of countries in Asia and Europe were identified as significantly underperforming in their commitment to mega-fauna conservation.

It seems to me that every country should strive to do more to protect its wildlife. Our index provides a measure of how well each country is doing, and sets a benchmark for nations that are performing below the average level, to understand the kind of contributions they need to make as a minimum.

We intend this conservation index to be a call to action for nations to acknowledge their responsibility to wildlife and we hope to encourage increased efforts and renewed commitment to biodiversity conservation. What really matters is the idea we have developed, rather than the detail: countries can be ranked in their commitment to conservation, and each country can and should strive to climb the rankings – the details of how the rank is calculated can surely be refined in future, but the idea of the ranking will hopefully endure.

Countries have achieved high scores in a variety of ways – some by setting aside vast protected area networks, others by allowing mega-fauna species to occupy high proportions of their landscape, and others by investing significant funding in conservation either domestically or internationally. Countries can improve their MCI scores in three ways. They can ‘re-wild’ their landscapes by reintroducing mega-fauna and/or by allowing the distribution of such species to increase. They can set aside more land as strictly protected areas. And they can invest more in conservation, either at home or abroad.

Excitingly, The Economist Magazine reported this year’s MCI index and presented a nice map of our findings:

Our hope is that the Economist, and others, will publish an annual update to provide a public benchmark for commitment to protecting nature’s largest, and, some would say, most charismatic wildlife. The way the index has been structured means that as countries of the world do more, the average benchmark will increase encouraging underperformers to try harder.

The Earth Touch News Network has made a video regarding this:

-

© 2016 Dawn Burnham

© 2016 Dawn Burnham