News

Out of the frying pan and into the fire?

David Macdonald reports on two WildCRU studies which, from different starting points, converge on the same alarming conclusion: while it’s a good thing that illegally traded wild animals are being confiscated at the national level and internationally under CITES regulations, it’s a bad thing that little is known about what happens to them next.

The first journey began when Chris Newman, Christina Buesching and I, together with our longstanding collaborators in China, Professors Youbing Zhou and Zhao-min Zhou, began quarrying into the customs records for confiscated wildlife rescued from illegal wildlife trade in Yunnan Province, China 2010-2015 (we were uniquely well-placed to do so because Zhao-min used to be a Wildlife Enforcement officer with the Yunnan Police!). That journey ended with our letter just published in Science. This is a tale of unintended consequences arising out of well-intentioned, but inadequately supported, legislation, worsened by conspicuously poor record keeping. In short1, (contrary perhaps to expectations) euthanasia is not permitted under China’s 2014 Regulation of rescue and asylum of terrestrial wildlife. Thus while all 155 native birds seized were liberated, few of 156 indigenous mammals were ever released; 41 slow lorises headed into the pet trade, 40 Asiatic black bears headed into tiny and inadequate pens and 69 primates were held in captivity indefinitely. Similarly, the vast majority of 12,473 native reptiles were sold into the pet, or restaurant trade. Sadly the 3,427 individuals from exotic species fared even less well – none being released or repatriated.

At best, this places a substantial burden on authorities to ensure good welfare standards for the animals for which they take responsibility but China’s wildlife sanctuaries and rehabilitation centres are not regulated by national laws, and the CITES 1997 Code of Practice 15 (Disposal of confiscated live specimens) recommendations are not implemented (although a CITES signatory nation). Not least, these facilities are often crammed full of captive-bred raccoon dogs and arctic foxes, abandoned as no longer wanted exotic pets. Consequently, most confiscated animals live short lives in crowded and inadequate enclosures. For instance, all of the 294 Malayan pangolins confiscated in Yunnan remained in sanctuaries until their premature deaths.

The second leg of the journey, published this week in Nature Conservation, began when my colleague Neil D’Cruze (on partial secondment to WildCRU from World Animal Protection) wondered what happens more broadly to 64,000 wild animals traded illegally and confiscated by CITES enforcement agencies between 2010 and 2014. Although this was the official number reported according to the Convention on international Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES) trade database, this figure, published in Nature Conservation, seems likely to be an underestimate. Only one in three countries Party to CITES actually provided any information (noting, with reference to the first leg of our journey that China does not), despite poaching of endangered species to supply the illicit global wildlife trade being estimated to be worth between $8-10 billion per year.

Information about the fate of these wild animals is not a formal CITES reporting requirement, consequently there are no figures describing just how many were euthanized, placed in captivity or returned to the wild. Undoubtedly many confiscated wild animals could be re-entering the wildlife trafficking industry: one might wonder, sadly, which fate is worse, to become an illegal pet or be rescued in a dismal facility.

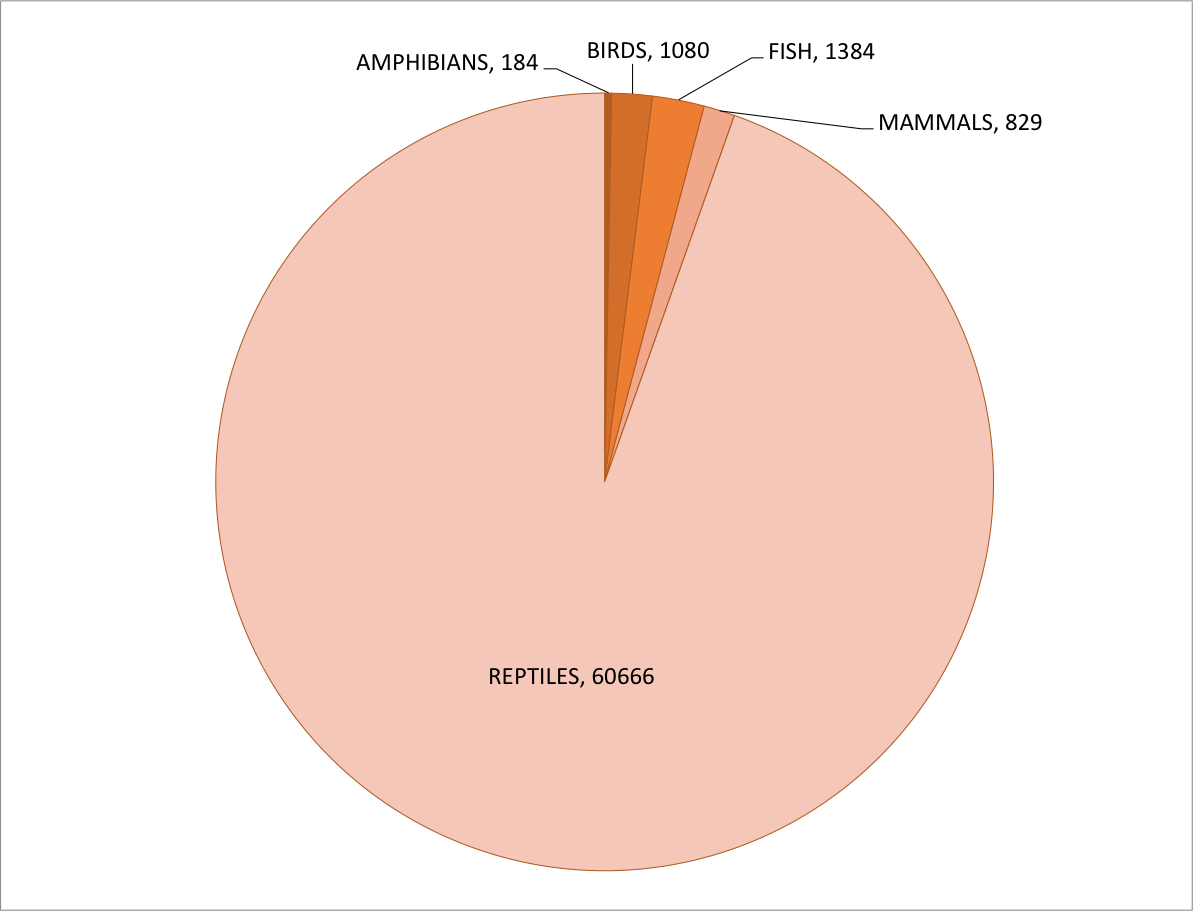

I fear this staggering number is just the tip of the iceberg. Only a relatively small proportion of wild animals involved with illegal trade is thought to be intercepted and reported by enforcement agencies– confiscation records were completely missing for 70% of countries Party to CITES. Given the rapidly growing global trends in illegal wildlife trade activity, it is highly unlikely that no live wildlife seizures were made in these other countries. The records that were provided show that, internationally, around 20% of all live wild animals reported as seized are currently of species considered to be threatened by extinction (See Figure). We strongly recommend that the CITES trade database should include information on the fate of all live wild animal seizures, so we know what happens to these animals, and we can reduce the risk of them re-entering the illegal wildlife trade. Once confiscated by authorities, it is then imperative that animals are either repatriated responsibly (risking another long trip in a crate), treated with appropriate regard for welfare, or euthanised to end their suffering.

Over-archingly, these combined studies highlight how conservation, legal enforcement and animal welfare do not exist as isolated concerns, but must operate in unison, to uniformly high standards, ensuring that all ‘rescued’ animals (native species and CITES protected alike) do not then go on to suffer an equally bad, or worse, fate to the cruel one that their confiscation was intended to prevent.

Figure 1: Proportion of live wild animals reported as seized by national enforcement authorities by taxonomic class 2010-2014

N= 64,143

Source: CITES WCMC trade database records. http://trade.cites.org/

Table 1: Top 10 species reported as seized by national enforcement authorities 2010-2014 collated from CITES records

| Rank | Species | Number of Animals Seized |

| 1 | False map turtle | 23,201 |

| 2 | Ball python | 12,172 |

| 3 | Russian tortoise | 7,115 |

| 4 | Ouachita map turtle | 4,500 |

| 5 | Bosc’s monitor | 2,630 |

| 6 | Senegal Chameleon | 1,705 |

| 7 | Radiated tortoise | 1,469 |

| 8 | Spur-thighed tortoise | 523 |

| 9 | Crab-eating macaque | 518 |

| 10 | Estuary Seahorse | 482 |

Source: CITES WCMC trade database records. http://trade.cites.org/

Zhao-Min Zhou, Chris Newman, Christina D. Buesching, David W. Macdonald and Youbing Zhou (September 1, 2016) Rescued wildlife in China remains at risk. Science 353 (6303), 999. [doi: 10.1126/science.aah4291]

D’Cruze, N and Macdonald D.W. (September 26, 2016) A review of global trends in CITES live wildlife confiscations Nature Conservation 15: 47-63 [doi: 10.3897/natureconservation.15.10005]

1Under the CITES Conf. 10.7 (Rev. CoP15; CITES 1997), government authorities confiscating live animals from illegal trade, have an obligation to deal with them appropriately. If the species concerned is listed on a CITES appendix (CITES 2016), there is a specific requirement (Article VIII) to {quote} “return the specimen to that State at the expense of that State, or to a rescue center or such other place as the Management Authority deems appropriate and consistent with the purposes of the present Convention”