Learning from the wolves: 30 years of science in action

September 30, 2025Written by Jorgelina Marino, EWCP Science Director

By the time the Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme began in 1995, the pioneering studies of Claudio Sillero and Dada Gottelli in the Bale Mountains had revealed that these wolves were fascinating, highly social creatures, perfectly adapted to Ethiopia’s Afroalpine habitats. Their work also showed, in a painful way, that rabies outbreaks could drive the species to the brink of extinction.

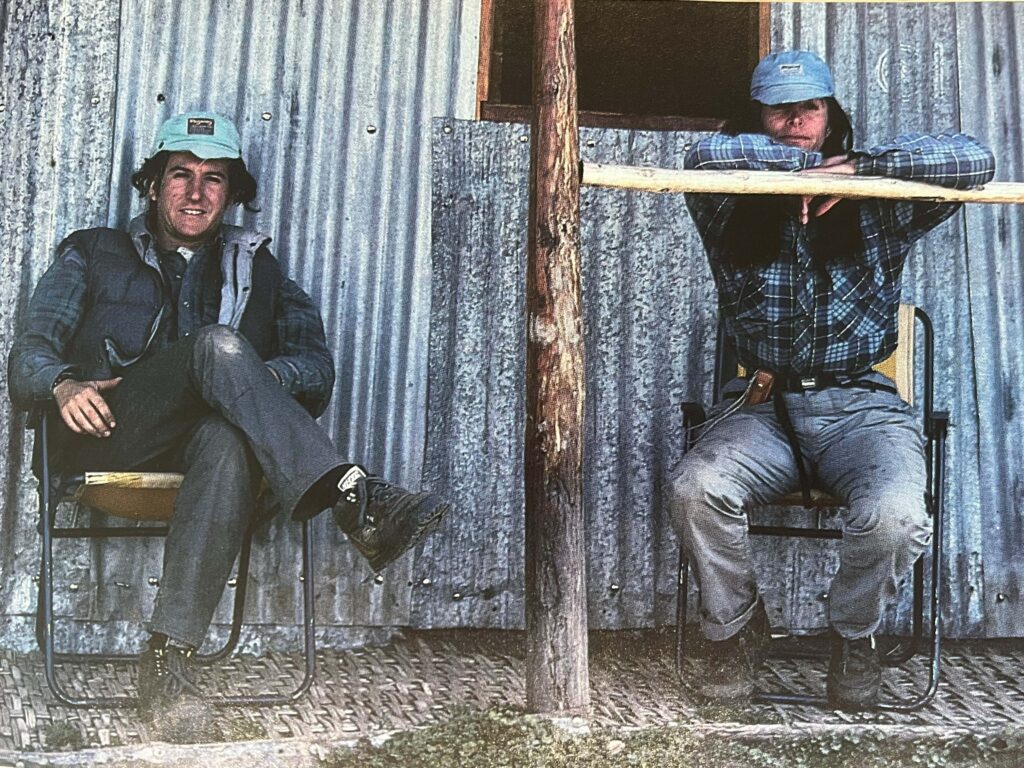

Claudio and Dada Gottelli at the Sodota camp, base for pioneering fieldwork in the Web Valley, Bale Mountains.

When I joined EWCP in 1997, our mission was clear: to understand how wolf populations functioned, when they were most vulnerable, and how disease spread. Could we detect outbreaks early and respond quickly? We were a small team – myself, Alo Hussein and only a few others – monitoring the packs first studied by Claudio and Dada in the Bale Mountains. These first efforts laid the foundations of a long-term database that has since transformed our understanding of the wolves. Throughout, Alo has mentored generations of wolf monitors, sharing his profound knowledge and colossal passion.

Alo Hussein working with Claudio in the field in the Bale Mountains.

By the late 1990s we knew Bale’s packs well but little about wolves elsewhere, as political instability had long prevented access. At last, we were able to visit nearly every mountain range in Ethiopia, finding wolves in all but one – the highlight of my professional life. These expeditions showed that each population faced unique challenges, yet habitat loss and the pressures of sharing land with people and livestock were the common threats. We also witnessed remarkable coexistence between wolves and local communities. Around this time, Zelealem Tefera conducted the first study outside Bale, demonstrating positive links between wolves and community-based conservation.

Jorgelina leading a survey in the Simien Mountains as EWCP’s operations expanded to the Northern region of Amhara.

In 2000, inspired by these findings, EWCP expanded nationwide. Fekadu Lema spearheaded work in the Amhara region, where he still leads a dedicated team of monitors and Wolf Ambassadors safeguarding as many wolves and packs as they can. This expansion brought vital insights: genetic diversity is spread across populations, and those populations of fewer than 20 wolves living in Afroalpine patches are bound to vanish. We learnt that every wolf family matters for the species’ survival.

©Katha Dittonbée

Each year, EWCP collects detailed demographic information from focal packs (see this year’s monitoring report). Long-term monitoring has revealed the pivotal role of breeding females, how social bonds hold packs together, and what drives the formation of new families. This knowledge underpins everything we do, from reactive vaccinations to targeted oral vaccination campaigns and community-led habitat restoration. Crucially, our understanding of endangerment and extinction, built through decades of monitoring, now shapes the Ethiopian wolf conservation strategy (Marino et al. 2024).

We know wolf populations can rebound quickly if given the chance: a well-protected den with a thriving litter of pups can turn the tide for a wolf population. Protecting dens, reinforcing packs, and even re-establishing wolf populations are essential for their future. Our monitoring and research aims are geared to provide all the evidence needed to guide these next steps. Since Claudio began studying them over 30 years ago, we have learnt that listening to the wolves is the best way to secure their survival.

Jorgelina with Getachew Assefa (L) and Girma Eshete (R) during fieldwork in Simien, Amhara.

This article is taken from EWCP’s 30th Anniversary Report.