News

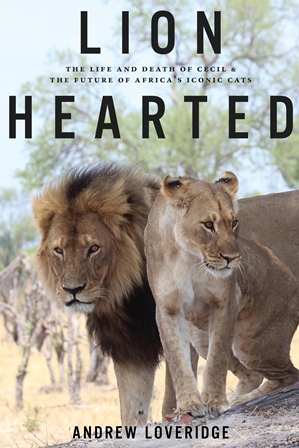

Lion Hearted: The Life and Death of Cecil & the Future of Africa’s Iconic Cats

New autobiography by Andrew Loveridge

Published by Regan Arts, Press Release excerpts with their permission:

“UNTIL THE LION HAS ITS OWN STORYTELLER, TALES OF THE LION HUNT WILL ALWAYS GLORIFY THE HUNTER.” — Zimbabwean Proverb

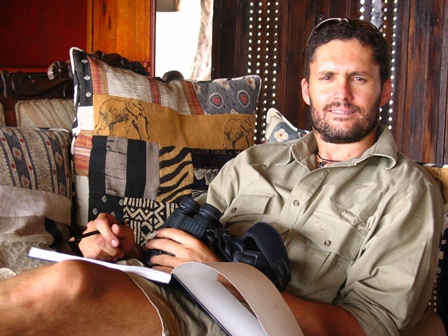

In 2015, an American hunter named Walter Palmer killed a lion named Cecil in Zimbabwe. The lion was one of dozens slain each year in the country, which legally licenses the hunting of big cats. But Cecil’s death sparked unprecedented global outrage, igniting thousands of media reports about the peculiar circumstances surrounding this hunt. At the center of the controversy was Dr. Andrew Loveridge, the zoologist who had studied Cecil for eight years. In Lion Hearted: The Life and Death of Cecil & the Future of Africa’s Iconic Cats, Loveridge pieces together, for the first time, the murky details of this beloved lion’s slaying. More than a gripping detective story, Loveridge’s memoir is an exploration of humanity’s relationship with the natural world and an attempt to keep this majestic species from disappearing.

In the tradition of Born Free and Gorillas in the Mist, LION HEARTED chronicles Loveridge’s long acquaintance with a host of charismatic lions as he unravels the complexities of their society. We learn that:

• Africa’s lion population is estimated to have shrunk by 43 percent in the last twenty years. There may now be as few as 20,000 wild lions across the entire continent—far fewer than the number of elephants.

• Male lions form “coalitions” that vie for control of territory and female prides. “The teeth and claws of a newly dominant male are invariably red with the blood of his rival’s children.” Cruel as this infanticide may seem, it prevents inbreeding and promotes genetic diversity.

• These apparently ruthless cats form deep emotional bonds. Hearing one lion “calling for his missing brother, for days on end, it was hard not to interpret this behavior as a distressing expression of loss.”

• A pride—“a sisterhood of mothers, daughters, sisters, and aunts”—exhibits military precision when hunting in formation (usually while a supervising male lets them do “the heavy lifting”).

• A female may fight a marauding male to the death to protect her children, but she also has “more subtle strategies . . . Feigning submission to the new male, a lioness becomes slinky and sinuous, oozing charm and sex appeal, tail curling snakelike across the male’s head and shoulders as she entices him to follow her. By mating with him, she distracts him and allows the other lionesses to escape with the pride’s cubs.”

• During several days of mating, a male and female may couple every ten minutes.

• Each lion’s whisker spots are unique, like human fingerprints.

• Lions lounge and sleep twenty to twenty-one hours a day.

• A lion’s low-frequency roar can be heard six miles away. The roar—a sequence of deep grunts amplified by a flexible throat bone—sounds nothing like that of the MGM lion, whose roar is actually a recording of a tiger.

• An adult male, which can weigh 495 pounds, needs a daily meal of between 11 and 17 pounds of meat—the yearly equivalent of 13 wildebeest, or 66,000 Big Macs.

Loveridge likens the lions’ internecine drama to Game of Thrones. “Our research has recorded remarkable stories of alliance, collusion, fratricide, tragedy, and conquest that rival the battles and intrigues of the Starks and Lannisters,” he writes. “The difference: lions do all this, not for greed, lust, or political power, but because of an evolutionary drive to pass on their genes to the next generation.”

Loveridge’s research team has tracked the movements of more than 700 lions, often from birth to death. In LION HEARTED, he introduces us to a cast of memorable cats. We meet:

• Stumpy Tail, who, despite her name, had “the dignity of an African queen . . . who ruled the pride and the valley with paws of steel.”

• Dynamite, a venerable coalition leader who, muscled out by younger males, sets off on an incredible 37-day, 137-mile journey to find a new home.

• Ulaka, who, even after killing a rival’s cubs, “picked up one of the small lifeless bodies, and carried it, almost tenderly, to the shade of a small blue bush. There he slumped, surveying the destruction he had wrought.”

• Kataza, who escapes Ulaka’s claws, and whom Loveridge twice saves from death at the hands of men. “It seemed such a waste that Kataza could survive so much and yet still succumb to a hunter’s bullet. To the hunter, no matter how exciting the hunt, this was just another lion. He would have no idea, as we did, of this animal’s amazing life story.”

• And, of course, there is Cecil. Dethroned in an epic battle, he forms an alliance with a former rival. He also becomes a favorite of photographers and tourists—until the fateful night when a Minnesota dentist and his hunting guide entice the trusting cat with a free meal.

Almost exactly two years after Cecil’s death, hunters killed his sons, Xanda and Sinangeni. “It is a fallacy that old males can be trophy hunted with little disruption to lion society,” writes Loveridge. “The death of one lion frequently results in the death of several others through starvation, infanticide, or conflict with other lions or people.”

Born and raised in Zimbabwe, Loveridge learned to love predators at the knee of his father, an eminent herpetologist who stored baby crocodiles in the family bathtub. Loveridge recounts his early days on a frontier where the people were sometimes as wild as the animals. After earning his doctorate at Oxford, he seized an invitation to study the lions of Zimbabwe’s Hwange National Park—bringing along his new bride, Joanne, to help him attach GPS collars to the cats. He finds that darting and tranquilizing a lion can be tricky—particularly when the lion wakes up while you’re carrying him.

When Loveridge begins his project in 1999, he accepts the theory that, by letting rich hunters kill a few lions, a country generates enough money to protect all wildlife. But his research reveals that wildlife authorities miscalculated the lion quota—and that hunters are luring lions to private land from protected reserves.

After winning a temporary ban on lion hunting in western Zimbabwe, Loveridge flies to a hunting convention in Reno, Nevada, hoping that conservation-minded sportsmen might fund his project. He receives a chilly reception—and no money—from conventioneers who discourage him from disclosing that trophy hunting is the chief cause of lion mortality. The hunting lobby represents “a hugely lucrative industry that believes its own propaganda,” he concludes. “It does not want to change.”

Loveridge’s opinion is reinforced when an anonymous whistle-blower sends him a grisly “snuff film” that captures an American hunter brutally slaying one of Loveridge’s study lions. Despite the official moratorium on hunting, no one is brought to justice. Emboldened, Loveridge shares his data on over-hunting with attendees at an international conservation summit. His report embarrasses Zimbabwean officials, who order his project shut down. Only after months of pleading does the government allow Loveridge’s team to return to their lions.

Some local leaders have accused the team of “allowing” lions to invade villages, where the cats have devoured livestock and children. Loveridge sympathizes with the villagers and has helped organize a unit of local guardians, the Longshields, who use GPS-trackers, mountain bikes, and noisy plastic trumpets to keep the lions at bay.

He understands why poor Africans might kill an animal, in retaliation for an attack, or to feed their families. While these Africans are prosecuted as poachers, he writes, “wealthy Westerners who pay large sums to hunt the same animals, sometimes in dubious circumstances, are called ‘sportsmen’ … There are starkly different rules for the elite and the poor. I wonder how long this will be acceptable to Africans.”

Cecil was the forty-second male study animal killed by a trophy hunter since Loveridge began his work. The backlash against Palmer, who reportedly paid $50,000 to bow-hunt a lion, showed that many already find trophy hunting unacceptable. Between July and September of 2015, Cecil was mentioned in over 94,000 articles and on over 695,000 social media posts. Jimmy Kimmel, Ricky Gervais, Roger Moore, and Mia Farrow were among the many public figures who mourned his loss. Loveridge offers several explanations for why “the Cecil incident” went viral. Whatever the reasons, the lion’s death turned into a “watershed moment in the history of hunting.” The US House of Representatives passed legislation to control trade in endangered or threatened wildlife, naming it, the Conserving Ecosystems by Ceasing the Importation of Large (CECIL) Animal Trophies Act. The continuing debate is reflected in President Donald Trump’s reversal of his own Interior department’s decision to lift the ban on importing body parts from what Trump termed “this horror show.”

Loveridge fears that, “as over-hunting and mismanagement deplete the ‘game’ in hunting areas, and these areas become less commercially viable, they will be abandoned as wildlife preserves, and surrendered to agriculture.” And yet, “banning lion trophy hunting will not halt the decline of Africa’s lion populations. Loss of habitat and conflict with livestock owners are the most important causes of lion population decline.”

“Lions are one of the most beloved animals on the planet,” Loveridge observes. “They are the national symbol of no fewer than fifteen countries . . . What child in the western world has not empathized with young Simba in The Lion King?” Given the lion’s cultural resonance, Loveridge proposes that the world help subsidize its survival.

“Most African states cannot afford the luxury of conserving wild animals,” he argues. “It seems unfair to burden the people of Africa, some of the poorest in the world, with the costs of protecting species that are globally important and globally valued.”

“To disentangle hunting from modern African conservation” won’t be easy, Loveridge admits. “But as a civilization that has the ingenuity to put people and machines into space, split the atom, and routinely send unimaginable amounts of information through the ether, surely we can think of a better way to save the wild animals we love besides killing them.”